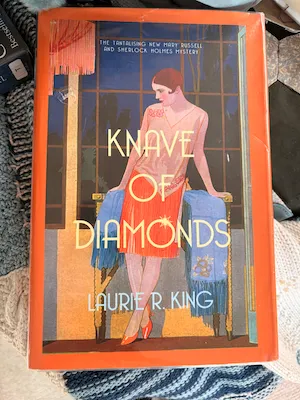

Roaring Girls

by Holly Kyte

Friday, November 29, 2024

I feel like I just read eight books. And they were all good. And I’d happily read all eight of them again in extended editions. Holly Kyte tells the stories of eight different women here; the first woman featured was born about 1585 and the last died in 1877. It would be an anachronistic mistake to call them feminists themselves but they all pushed against the boundaries of what women were meant to do and be in their times and the way that they moved of those boundaries made life better for all of us who came along later.

I want to write down all their names so I can remember who they all were later. I only knew two of the names before I began reading; and I was only really properly familiar with one of the stories. This is a super quick summary of what I can remember of them from memory:

Mary Frith, also known as Moll Cutpurse, is the Roaring Girl from whom the book takes its title. She was a London pickpocket who appeared on stage in an age when only men were allowed to do so, and dressed as a man to do so. Margaret Cavendish, who published her autobiography among many other works, Mary Astell, champion of women’s education. Charlotte Charke, actress and playwright who often went by Charles Brown; Hannah Snell who joined the navy as James Grey. Mary Prince’s was the one story I had come across before. She was born a slave in Bermuda and became the first black female slave to have her biography published in Britain. Anne Lister was the other character I’d heard of, but I’d never read the details of her life as ‘the first modern lesbian’ before this. The book concludes with Caroline Norton whose long drawn out battle with her abusive husband resulted eventually in changes in the law allowing women to divorce and have custody of their children.

Reading these stories, no matter how informed you think you are, it’s a shock to realise how little rights women had in the past. How women were the property of their husbands and couldn’t own any of their own possessions for example. There are a few delightful parts of the book where the various women play the law off against itself. Mary Frith had a delightful trick where she would run a fraud as a single woman but then revert to a married woman with no legal existence when the law caught up with her. But on the other hand it was interesting to find out that Hannah Snell would likely have faced nothing more than discharge if she had been discovered as a woman in the military; revealing herself as female would have been an easy way to avoid punishment. What’s interesting is that she, and other military women, did not give themselves up in these circumstances, the conclusion being that the punishment was less horrible than getting sent straight back to live as a woman.

The modern reader wants these women to be progressive but not all of them are. Anne Lister’s treatment of the people she considered her wives involves exploiting them in the same way as a man would have done. Caroline Norton actively opposed the burgeoning ‘equalist’ movement rather than joining them. Some of the details are uncomfortable. It’s all interesting and informative, and a lot of it makes me rage. And it’s well worth reading.