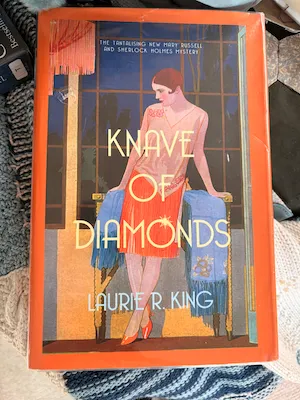

Knowing What We Know

by Simon Winchester

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Well, I finished this at the end of January and I haven’t known where to start with writing something down about it. I’ve been thinking about it quite a bit. Usually if I leave something as a background process in my brain for a while something vaguely coherent pops out. It feels a little ironic that a book subtitled “How we acquire, retain and communicate knowledge from ancient times to the era of big data” is proving to be something I find difficult to communicate about! And also maybe to retain. Anyway I now feel it’s getting in the way of me retaining knowledge of the books I’ve read since because I want to post about this one before I get to those. And maybe then it’s also getting in the way of me reading books because I don’t like to carry a backlog.

Page by page it was a super interesting book. There’s hundreds of anecdotes, mostly facts in fact, about information here. The book is at it’s best, and it’s most memorable when the author is speaking from his personal experience. An account of the fallout from the Bloody Sunday massacre that he reported on in 1972 and testified in its two enquires with very different results - the first just after the events exonerating the British Army and the second in 1998 condemning them - was the standout passage of the book for me. It comes just after an account of how young Chinese students today don’t know ‘Tiananmen Square’ as signifying anything beyond than the geographical location, I was aghast at that and then quickly set straight on how knowledge is manipulatable all around the world.

To me it seemed that it was an all encompassing sort of a book, but it shone best when it zoomed in on a tiny aspect of knowledge. Aspects of it have seeped into my brain and I think they’ll keep occuring to me in the years to come. And the books going to stay on my shelf for reference. But in another way the whole thesis of the book is kind of forgettable. We’re a curious species, we obtain knowledge and we somehow forget we ever didn’t have that knowledge. The book reaches as far as the dawn of the ChatGPT era and here’s a quote related to that:

If there is no pressing need to know much about anything, nor much of a need to remember anything, then a previously unimaginable corollary is on the horizon. There will very soon be no particular need to be intelligent at all.

Which is rather chilling. I certainly don’t want a machine to do the thinking for me; and I don’t think AI is “intelligent” really. But here I am forgetting the details of the book I read just a handful of weeks ago already. I guess an LLM could have churned out a much better summary of this book for you and maybe I should pay more attention if I want to keep up with them. But this is what I have. It’s my impressions of the book and what made it valuable to me, and that interface between the printed page (which is increasingly my preference once again by the way) and the squishy malleability of my brain is still something only I can come up with.